Wound care is the set of practices and clinical decisions that protect damaged skin, prevent infection, and promote timely wound healing. Effective wound management reduces complications, shortens recovery time, and lowers the risk of chronic wounds such as diabetic foot ulcers and pressure injuries. This guide explains the types of wounds you may encounter, the biological stages of healing, practical home-care steps, and evidence-informed choices for wound dressing types and advanced therapies.

What Are the Different Types of Wounds and Their Causes?

Wound types define risks, expected healing timelines, and appropriate management strategies; classifying wounds (acute vs chronic) clarifies when to focus on simple barrier care versus comprehensive chronic wound management. Acute wounds typically result from trauma or surgery and usually follow predictable healing phases with low complication risk when properly managed. Chronic wounds—such as venous ulcers, arterial ulcers, pressure injuries, and diabetic foot ulcers—fail to progress through normal stages of wound healing and require assessment for underlying factors like poor perfusion, infection, or metabolic deficits. Identifying the wound type early guides choices about dressings, debridement, infection control, and whether referral to specialist clinics or vascular assessment is needed. Understanding causes and risk factors helps prioritize prevention strategies and informs decisions about offloading, compression, or vascular studies.

How Are Acute and Chronic Wounds Defined and Classified?

Acute wounds are skin disruptions that progress through the expected healing phases within a predictable timeframe, generally closing within a few weeks when uncomplicated. Chronic wounds are those that do not follow normal healing trajectories—clinically many guidelines use thresholds such as lack of meaningful progress after 4–12 weeks (rather than 4–8 weeks)—to prompt reassessment and specialist input. Classification systems include pressure injury staging, wound depth descriptors (partial vs full thickness), and etiologic categories (venous, arterial, neuropathic, traumatic, surgical), each influencing management priorities like offloading for neuropathic ulcers or vascular workup for arterial disease. Accurate classification supports targeted interventions—compression for venous ulcers, improved perfusion for arterial disease, and glycemic optimization for diabetic wounds—reducing the risk of infection and tissue loss. Recognizing classification also sets expectations for patients and caregivers about healing timelines and likely next steps.

What Are Common Causes of Wounds Like Cuts, Burns, and Ulcers?

Wound etiology spans mechanical trauma (cuts and scrapes), thermal injury (burns), surgical incisions, pressure-related tissue breakdown (bedsores), and disease-related ulceration (diabetes, venous insufficiency, arterial occlusive disease). Traumatic wounds often require cleaning, hemostasis, possible suturing, and tetanus vaccination assessment; prevention includes safe tool use and protective equipment. Burns vary by depth and require specific thermal injury management to limit progression, infection, and scarring, while chronic disease-related ulcers reflect repetitive stress, neuropathy, or poor circulation and demand systemic evaluation. Prevention tips map to cause: footwear and foot checks for diabetes, pressure redistribution and regular repositioning to prevent pressure injuries, and compression plus leg elevation for venous disease. Understanding cause guides both immediate wound care and long-term prevention strategies.

What Are the 5 Stages of the Wound Healing Process?

Wound healing unfolds through a sequence of coordinated biological stages that restore tissue integrity; clinicians and caregivers use these stages to interpret clinical signs and adjust wound management accordingly. The five-stage framework clarifies early coagulation and hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation (granulation and epithelialization), and remodeling (maturation), linking cellular events to observable signs and expected timeframes. Recognizing which stage a wound is in helps determine suitable interventions—protecting early clots during hemostasis, monitoring for infection during inflammation, maintaining moisture balance during proliferation, and minimizing tension during remodeling to improve scar outcomes. This understanding supports appropriate dressing selection and decisions about interventions like debridement, antibiotics, or referral for advanced therapies when healing stalls.

| Stage | Key Cellular Events | Clinical Signs / Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Hemostasis / Coagulation | Platelet aggregation, clot formation, fibrin scaffold | Immediate to hours: bleeding control, visible clot or scab formation |

| Inflammation | Neutrophil then macrophage influx, cytokine release | Days 1–4: redness, heat, swelling, serous exudate; pain may peak |

| Proliferation (Granulation) | Fibroblast migration, collagen deposition, angiogenesis, epithelialization | Days 3–21: pink granulation tissue, reduced bleeding, wound contraction |

| Early Remodeling | Collagen reorganization, decreased cellularity, tensile strength building | Weeks to months: gradual firmness, fading erythema, scar formation |

| Maturation / Long-term Remodeling | Cross-linking of collagen, scar maturation | Months to years: continued tensile strength gains, cosmetic improvement |

This table condenses cellular actions into clinical expectations and helps clinicians and caregivers link observation to next-step care, such as when to prioritize infection surveillance versus moisture management.

What Happens During Hemostasis and Inflammation Stages?

Hemostasis begins immediately with vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation to form a fibrin clot that halts bleeding and provides a provisional matrix for cell migration; protecting this early scaffold prevents re-bleeding and infection. The inflammation stage follows as neutrophils clear debris and bacteria, then macrophages orchestrate transition to repair by releasing growth factors that recruit fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Clinically, inflammation presents with erythema, warmth, swelling, and serous or sanguineous exudate; these signs must be distinguished from infection by patterns—progressive worsening, purulence, and systemic features suggest infection rather than normal inflammatory response. Care during these stages prioritizes gentle cleaning, avoiding disruption of early clot and granulation tissue, and considering tetanus vaccination or topical antiseptics when appropriate to reduce bacterial load. Proper early management sets the stage for effective proliferation and lowers the risk of chronic wound conversion.

How Do Proliferation and Remodeling Support Tissue Repair?

During proliferation, fibroblasts synthesize collagen and extracellular matrix while angiogenesis restores perfusion and epithelial cells re-cover the wound surface, producing healthy granulation tissue that fills defects. Moist wound healing principles—maintaining a balanced moist environment—support epithelial migration and reduce scarring while dressings that manage exudate protect fragile new tissue. Remodeling gradually replaces type III collagen with stronger type I collagen and aligns fibers with mechanical forces, improving tensile strength though scars rarely regain full pre-injury strength; offloading and gradual tissue loading can influence final scar quality. Clinically, interventions in this phase include continued exudate management, pressure redistribution for ulcers, and rehabilitation to restore function while monitoring for hypertrophic scarring or contractures that may need specialist input.

How Can You Provide Effective Wound Care at Home?

Safe home wound care follows clear steps that control bleeding, reduce contamination, and protect tissue while monitoring for signs of infection or delayed healing; following evidence-based cleaning, dressing, and monitoring techniques reduces complications. Start by controlling bleeding with direct pressure and elevation, then clean using normal saline or clean water to remove gross contamination; antiseptic solutions are reserved for heavily soiled wounds or where infection risk is high. Appropriate dressing selection balances moisture retention and exudate control—thin adhesive dressings for minor cuts, moisture-retentive dressings for clean granulating wounds—and securement should avoid excessive tension or pressure. Regular dressing changes with hand hygiene, assessment for odor, worsening pain, or increased drainage, and keeping tetanus status current are key steps that reduce infection risk and support timely healing.

Wound care at home follows a concise step-by-step routine:

- Stop bleeding and protect the wound: Apply clean direct pressure, elevate, and cover with sterile gauze.

- Clean gently: Irrigate with saline or clean water; avoid harsh scrubbing that disrupts tissue.

- Dress appropriately: Choose a dressing that matches exudate level and wound stage; secure without constricting.

- Monitor and seek help: Check daily for increasing redness, pus, fever, or non-healing beyond expected timeframes.

These steps provide a practical framework that emphasizes patient safety and vigilance; if any red flags appear, escalate to professional care for evaluation, culture, or antibiotic therapy as indicated.

What Are the Best Practices for Cleaning and Dressing Wounds?

Cleaning aims to reduce bioburden and debris without injuring viable tissue; isotonic saline is the preferred first-line irrigant for most wounds because it is safe, non-cytotoxic, and effective at flushing contaminants. Antiseptic solutions (chlorhexidine, povidone-iodine) may be appropriate for heavily contaminated wounds or where infection risk is high but should be used judiciously due to potential tissue toxicity. Dressing selection is driven by wound exudate and stage: moisture-retentive dressings (hydrocolloid) support epithelialization, foam dressings absorb moderate exudate, and alginate dressings handle heavy drainage while forming a gel that maintains a moist interface. Techniques for safe dressing changes include hand cleansing, minimal disruption of granulation tissue, gentle removal of adherent dressings with saline, and documenting changes in size, depth, and exudate to detect stalled healing early.

How Do You Recognize Signs of Wound Infection Early?

Early recognition of infection differentiates normal inflammatory signs from pathological processes that require antibiotics or drainage; local indicators include escalating pain, increasing erythema that spreads, warmth beyond the wound margin, purulent or malodorous discharge, and increasing exudate. Systemic signs—fever, chills, tachycardia, or new confusion—suggest bacteremia or severe infection and warrant urgent medical evaluation. For people with diabetes or immunocompromise, smaller clinical changes may reflect more serious infection due to impaired immune responses; diabetic foot ulcer care emphasizes vigilant daily inspection and lower thresholds for contact with healthcare providers. When infection is suspected, clinicians may perform wound cultures, start targeted antibiotic therapy, assess for abscess requiring drainage, and consider imaging or vascular studies depending on context.

What Types of Wound Dressings Are Available and When Should They Be Used?

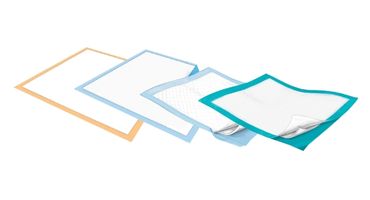

Understanding wound dressing types and their core properties helps match wound needs—absorption, moisture retention, adherence, and antimicrobial action—to the right product, improving outcomes in both acute and chronic wound care. Major dressing categories include gauze, transparent films, hydrocolloids, foams, alginates, and antimicrobial or collagen-based dressings; each has distinct strengths and limitations for exudate management, protection, and frequency of change. Choosing dressings involves assessing wound stage, exudate level, infection risk, and anatomical location, and adjusting choices as the wound progresses through hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. Practical decision-making also considers patient factors like mobility, skin sensitivity, and access to supplies, and when dressings are insufficient, clinicians may escalate to advanced therapies such as negative pressure wound therapy or bioengineered skin substitutes.

Before the table, here is a quick comparison to guide dressing selection: the table below summarizes common dressing categories, their primary properties, and best use cases or contraindications to support practical decision-making.

| Dressing Type | Primary Properties (absorptive, adherent, moisture-retentive) | Best Use Cases / Contraindications |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrocolloid dressing | Moisture-retentive, non-absorptive to low absorption | Best for low-moderate exudate, promoting epithelialization; avoid on clinically infected wounds |

| Foam dressing | Absorptive, cushioning, adhesive or non-adhesive | Good for moderate exudate and pressure-prone sites; change based on saturation |

| Alginate dressing | Highly absorptive, forms gel on wound contact | Ideal for heavy exudate and bleeding wounds; contraindicated on dry wounds |

| Transparent film | Non-absorptive, adherent, barrier to bacteria | Useful for superficial abrasions and IV sites; not for exuding or infected wounds |

| Gauze | Variable absorbency, inexpensive | Useful for packing deep wounds or short-term coverage; frequent changes required |

| Antimicrobial dressings | Contain silver, iodine, or antiseptic agents | Consider when infection is suspected or high-risk wounds; monitor for sensitivity |

How Do Hydrocolloid, Foam, and Alginate Dressings Differ?

Hydrocolloid dressings create a moist, occlusive environment that supports epithelial cell migration and are useful for low to moderate exudate on intact peri-wound skin; they are generally easy to apply but should be avoided on clinically infected wounds due to occlusion. Foam dressings combine absorption with cushioning, making them suitable for moderate exudate and pressure areas where padding matters; adhesive foams offer secure placement while non-adhesive foams need secondary fixation. Alginate dressings, derived from seaweed, excel at managing heavy exudate and can conform to irregular cavities while forming a gel that supports a moist healing environment; they require secondary dressing and are not appropriate for dry wounds. Each dressing type has contraindications and application nuances that influence frequency of change, monitoring needs, and overall wound management strategy.

Which Dressings Are Best for Chronic vs. Acute Wounds?

Acute wounds generally prioritize barrier protection, infection prevention, and simple moisture balance—sterile gauze or simple adhesive dressings suffice for clean minor lacerations, while hydrocolloids may support epithelialization of clean superficial wounds. Chronic wounds require dynamic management focused on moisture balance, biofilm control, and addressing underlying causes; choices often include absorptive foams, alginates for heavy exudate, and advanced antimicrobial or collagen-based dressings when infection or stalled healing is present. For venous leg ulcers, compression combined with appropriate dressings is essential, while neuropathic diabetic ulcers need offloading plus moisture management and close vascular and glycemic assessment. When standard dressings and local care fail to promote progress, referral for advanced treatments such as debridement, negative pressure wound therapy, or specialist assessment is indicated.

What Are Advanced Treatments and Solutions for Chronic Wound Care?

Advanced chronic wound therapies aim to correct underlying deficits—poor perfusion, persistent biofilm, or tissue loss—using targeted modalities such as negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), and bioengineered skin substitutes, each with specific mechanisms, indications, and limitations. NPWT applies controlled subatmospheric pressure to remove exudate, reduce edema, and stimulate wound-edge perfusion and microdeformation that promotes granulation. HBOT increases dissolved oxygen in plasma to enhance fibroblast and neutrophil function in hypoxic wounds, while bioengineered skin and growth-factor products supply structural matrix or signaling molecules to support tissue regeneration in complex defects. Selecting among these options depends on wound etiology, perfusion status, infection control, and response to standard care; multidisciplinary assessment helps identify which modality—or combination—offers the best chance of healing.

Below is a concise comparison of advanced options to guide referral and expectation-setting.

| Treatment | Mechanism of Action | Typical Indications / Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) | Removes exudate, reduces edema, applies microdeformation to stimulate granulation | Indicated for large open wounds, post-debridement cavities; requires device access and regular dressing changes; contraindicated with untreated osteomyelitis or exposed vital structures |

| Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT) | Increases tissue oxygen tension, enhances oxidative killing and collagen synthesis | Consider in refractory diabetic foot ulcers and certain hypoxic wounds; limited by availability, cost, and contraindications like untreated pneumothorax |

| Bioengineered skin substitutes | Provide extracellular matrix, cellular components, or growth factors to support tissue formation | Used for non-healing ulcers and surgical defects; effectiveness varies by product and costs; may require repeated applications |

| Growth factor therapies | Deliver signaling proteins to stimulate cell proliferation and angiogenesis | Applied when local growth factor deficiency suspected; regulatory and cost considerations limit routine use |

How Does Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Work?

Negative pressure wound therapy uses a sealed dressing connected to a pump that applies controlled suction to the wound bed, removing excess fluid and promoting a microenvironment conducive to granulation tissue formation. Mechanically, NPWT reduces interstitial edema, increases perfusion at wound edges, and exerts microdeformation that stimulates cellular proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition. Devices range from portable units for ambulatory use to larger systems for complex inpatient wounds, and protocols typically require dressing changes every 48–72 hours depending on exudate and device type. Contraindications include untreated necrotic tissue with eschar, active bleeding, or exposed blood vessels without protective layers; monitoring for bleeding and device seal integrity is essential during therapy to avoid complications.

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy: Mechanisms and Clinical Applications

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) promotes healing by evenly applying negative pressure on the surface of the wound. The system consists of a sponge, a semiocclusive barrier, and a fluid collection system. Its effectiveness is explained by four main mechanisms of action, including macrodeformation of the tissues, drainage of extracellular inflammatory fluids, stabilization of the environment of the wound, and microdeformation. Rarely will complications linked to NPWT occur, but special care must be taken to prevent events such as toxic shock syndrome, fistulization, bleeding, and pain. New NPWT modalities have been recently developed to make NPWT suitable for a wider variety of wounds. These include NPWT with instillation therapy (NPWTi-d), different cleansing options, and application of NPWT on primarily closed incisions. Finally, vacuum-assisted wound closure therapy has been demonstrated to be efficient for various clinical settings, such as the management of diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcerations, chronic wounds, and skin grafts.

What Role Does Nutrition and Oxygenation Play in Healing Chronic Wounds?

Nutrition and oxygenation are foundational systemic influences on wound healing: adequate protein, vitamin C, zinc, and calories supply substrates for collagen synthesis and immune function, while sufficient tissue oxygenation enables oxidative bacterial killing and collagen cross-linking. Protein-energy malnutrition impairs fibroblast proliferation and delays wound closure, and deficiencies in micronutrients like vitamin C and zinc are associated with reduced collagen formation and slower healing. Clinically, assessing nutritional status and addressing deficits—through dietary optimization, supplementation, or referral to a dietitian—improves outcomes, particularly in chronic wound care where metabolic demand is sustained. Optimizing oxygen delivery by treating anemia, improving perfusion, and considering adjuncts like hyperbaric oxygen for selected hypoxic wounds complements local measures to restore effective tissue repair.

When Should You Seek Medical Attention for Wound Complications?

Recognizing red flags and clear escalation criteria prevents deterioration and guides timely interventions—antibiotics, surgical debridement, or specialist referral that may include vascular, infectious disease, or wound care teams. Urgent medical attention is warranted for systemic infection signs (fever, rigors), rapidly spreading erythema or lymphangitic streaking, uncontrolled bleeding, exposed bone or tendon, or severe pain disproportionate to the wound appearance. Wounds that fail to show measurable improvement after approximately 4–12 weeks despite appropriate local care should be re-assessed for underlying contributors like ischemia, infection, or metabolic dysfunction and considered for referral to specialized chronic wound services. Special populations—people with diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, or immunosuppression—require lower thresholds for professional evaluation due to higher risk of rapid deterioration and poorer outcomes.

Ready to take the next step in better wound care?

Explore how Medsitis can support you with reliable guidance, high-quality products, and expert resources. Contact us today.